When I first started doing press for True Born, one of the questions I was most surprised by (which became ubiquitous, by the way) was this: Are you a Plotter, or a Pantser?

If you’re a little lost, allow me to translate. The interviewers were asking if, during my writing process, I liked to ‘fly by the seat of my pants’ — just going along with the whimsy of the writing process — or, alternatively, did I meticulously plot out my novels?

The truth, of course, is never a straight line. At the time, I believe I answered something to the effect of, “I’m in between.” After all, I had a full, three-novel arc floating around in my head. I plotted that out, then worked backwards to fill in the gaps.

Much has changed since True Born was published in 2016. I’ve written five novels since then, and with each book, I’ve learned so much. Each, I would argue, is better than the last. One of the reasons why that is so is because I finally learned that plotting — meticulously, painstakingly — is essential to developing a great novel.

The scene-by-scene blueprint has simply become the walk-in closet by which I’m able to try on all the outfits I could ever want.

Pantsing It

“Pantsing” involves working solely on the level of intuition and creativity. That’s great if your goal is to write the next On The Road (1957 classic American text, in case you’ve never read it). This kind of plot development involves using your deep connection to the text or writing process to spur the text’s creation. The Beats, like Jack Kerouac (author of On the Road) were famous for this use of autonomous creation.

To my mind, that’s a little like trusting your brain to act like ChatGPT to spit out a perfectly formed novel. Maybe it happens. Maybe it’s gobbledygook.

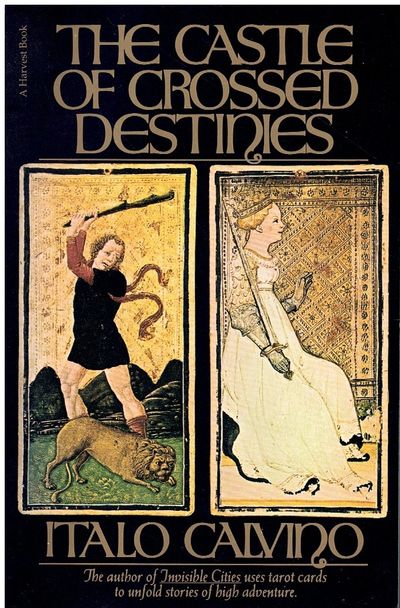

In its most successful incarnation, writers can use this kind of “endlessly inspired” model as the plot structure itself — like in Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973). (In this novel, two different decks of tarot cards are used as a device to help characters, unable to speak, communicate, while the cards’ stories begin to spin out of control). The point of this Italian postmodern masterpiece is literally to playfully confront the tensions between structure (in the form of tarot cards, images) and the generation of meaning (which is infinite).

VS. Being in Control

But for most of us, especially those of us who are writing and publishing commercial genre fiction (yes, sci-fi and romantasy count!) planning is key. Genres rely on conventions, after all. Conventions rely on tropes and plots. If you’re not satisfying these for readers, you’re likely going to a) turn off your readers, and/or b) not produce much worth reading.

That’s not to say that once your MS is plotted you don’t make changes. Recently, I plotted out an entire novel (more on this delicious thing later). I decided to plan out each scene in detail before writing — not my usual M.O., let me tell you — and it took a looooonnng time. That’s because for this urban fantasy, which follows many story lines and characters at once, plot is the pin that holds the entire book together.

Still, it was only after I started writing the book that I figured out what really makes the story tick. I went back to the plot structure, tweaked a few scenes, and went on my merry way. As I’m writing, I’m still changing scenes, deleting others. The scene-by-scene blueprint has simply become the walk-in closet by which I’m able to try on all the outfits I could ever want.

In other words, just because you plot doesn’t mean you don’t have more to learn from your narrative, or the process of writing itself. It’s not just a mechanical act — you’re still creating.

And so. Back to plotting.

Can you imagine Sarah J. Maas making up Crescent City as she went along? How would she keep track of all those characters and storylines, how they intersect and change one another? How the heck would she get to the complete and utter mindf&*ck of a cliffhanger at the end of book two? (In my opinion, one of the most daring and unbelievable moves in any fiction series, bar none. That woman is a genius).

The moral of the story here is that there is room in every story for pantsing. But also remember this: as readers, we are already hardwired into following the basic conventions of plot. Our brains require these in any story, so we’re automatically going to lean into plotting, whether we like it or not.

After all, a plot by any other name is just a structure, like margins or a book spine, that would read as sweet.

Images: From: Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies, 1973.; Cover, Jack Kerouac, On the Road (Pan edition, 1961); Cover, The Castle of Crossed Destinies.

Leave a comment